French-Canadian and Métis Heritage at St Boniface Museum

Le Musee de Saint Boniface in the French Quarter of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, showcases French-Canadian and Métis heritage and history

Note: The St. Boniface Museum is closed as of June 26, 2024 for necessary renovations and plans to reopen in 2026. In the meantime, the gift store and a small Louis Riel exhibit has been set up in the former St. Boniface City Hall. Read my post St. Boniface Museum Louis Riel Exhibit.

The Saint Boniface Museum in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, showcased objects related to the heritage of French-Canadian and Métis people in western Canada. It also contains items related to the historic contributions of First Nations and religious communities, and boasts the largest collection of Louis Riel artifacts in Canada. It is an excellent place to learn and discover more about French-Canadian and Métis culture and history.

The museum is located in the neighbour of St. Boniface across the Red River from Winnipeg’s downtown. The area is know as Winnipeg’s French Quarter.

The museum building itself is a primary artifact. It is the oldest remaining structure in Winnipeg and the largest oak log building in North America. It is a former Grey Nuns’ convent and was built between 1845 and 1851. It once served as the first hospital in Western Canada. At other points in its history it was a school for boys and girls and a boarding school for girls.

The building was constructed using a technique known as Red River Frame construction. Squared oak logs were laid on a fieldstone foundation. Upright timbers with grooves cut into the sides were added. Squared logs with tenons at each end were stacked horizontally, the tenons sliding into the grooves. The Grey Nuns vacated the building in 1956. The Museum opened in 1967.

The museum tells the history of the fur trade and the voyageurs, French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs by canoe. It also tells the story of early French-Canadian life in what was then the Red River Settlement.

One of the stories told in detail is that of Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière and Marie-Anne Gaboury. Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière was typical of the first French Canadians who settled in the Canadian West. Around 1800, he was a voyageur travelling between Montreal and Fort William, which is now part of Thunder Bay, Ontario. He married a First Nations woman “according to the custom of the country” and had three daughters. When his contract was up, he returned to Montreal and married Marie-Anne Gaboury. He returned west. Defying convention, Marie-Anne went with him. They eventually settled in the newly established Red River Settlement in 1815. Marie-Anne was not a typical woman of her time. She adapted to her husband’s nomadic lifestyle, travelled with him across the prairies, and learnt to be self-sufficient during his long absences on hunting trips.

Red River carts were two-wheeled carts made entirely of wood and animal hide. Nails, which were expensive or unavailable, were not used in their construction. The carts were drawn by oxen, horses or mules, and were used primarily for transporting furs.

The origin and development of the Métis nation is one of the themes at the Museum. The Métis were children of the fur trade, born of marriages between French-Canadian voyageurs and First Nations women. They carved a niche for themselves in the fur trade and developed their own identity.

There are a number of artifacts in the Museum relating to religious life. There is a section containing drawings, old photographs, models and other information about the history of the St. Boniface Cathedral, located just down the street from the Museum. The first church was built in 1818. Building of a slightly larger second church began in 1819 and completed in 1825. It became the first Cathedral and was known as the Mother Church of Western Canada. The building was damaged in the flood of 1826. The third church, built between 1831 and 1839, was destroyed by a fire in 1860. The fourth church opened for worship in 1863. It was torn down over thirty-five years later when the diocese outgrew the space.

The fifth church was inaugurated in 1908. It was the most elaborate Roman Catholic Cathedral in Western Canada and an excellent example of French Romanesque architecture. It was declared a minor basilica in 1949. The church was gutted by fire in 1968. Only the stone walls remained. Today’s church has been built behind the stone façade, incorporating the sacristy, façade and walls of the former basilica. The ruins remain an excellent example of French Romanesque architecture.

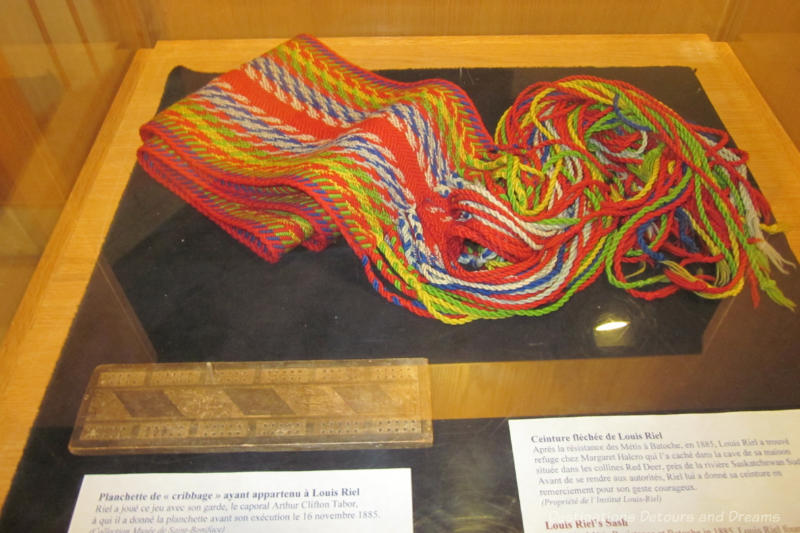

The story of Louis Riel is the heart of St. Boniface Museum. There is an exhibit on his life and the museum contains many artifacts which belonged to him or are connected with him. Louis Riel was a Métis leader and is known as the father of Manitoba. He was born in 1844. His father, also named Louis Riel, was Métis. His mother was Julie Lagimodière, daughter of Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière and Marie-Anne Gaboury. He was educated by the Grey Nuns and the Christian Brothers. He went to Montreal for further education.

In 1869, the Hudson Bay Company agreed to sell Rupert’s Land to the Dominion of Canada. Rupert’s Land was a huge area. It encompassed what is now northern Québec and Labrador, northern and western Ontario, all of Manitoba, most of Saskatchewan, south and central Alberta, and parts of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. A 1670 royal charter had given the fur trading company exclusive rights to trade and colonize all lands containing rivers following into Hudson Bay. In preparation for the land transfer, the Dominion sent out land survey crews. The Métis formed the Métis National Committee to protect their rights. Louis Riel became a leader within that organization. They stopped the surveys, seized Upper Fort Garry and formed a provisional government. Under Riel’s leadership an agreement was reached with the Canadian government which resulted in Manitoba becoming a Canadian province under conditions reserving 1.4 million acres of land for children of Métis residents and guaranteeing Manitoba would be officially bilingual.

Riel’s story after that is more complex than I can easily summarize, but I will provide a few highlights. He was regarded as a hero in Québec and a murderer in Ontario. During the time of the provisional government, Thomas Scott, an Orangeman from Ontario, had been sentenced to death by an associate of Riel’s. With financial aid from the Canadian government, Riel went into a short voluntary exile in the United States. He later served briefly as a representative of Manitoba’s Provencher riding in the federal government. In 1875, the federal government granted him amnesty for crimes he’d never been convicted of in court. The amnesty was conditional on five years banishment from “her Majesty’s Dominion.” He suffered a nervous breakdown shortly after exile, He later settled in Montana, married a Métis woman, became a school teacher and took up U.S. citizenship.

In 1884, a Métis group in the Saskatchewan Valley asked him to help them protect their rights. He and his family made a temporary move to Batoche, Saskatchewan. What started as peaceful protests became violent in 1885. The Métis lost patience waiting for Canada to negotiate and drafted a “Revolutionary Bill of Rights”, asserting rights to their farms and other demands. Upon hearing the Canadian government was sending 500 soldiers in response, the Métis seized the parish church and formed a provisional government with Riel as President. After two months of fighting, the Métis were defeated. Riel surrendered. Riel was convicted of treason. The trial was controversial with Riel at odds with his lawyer. The jury recommended clemency, but none was forthcoming. Riel was hanged November 16, 1885.

Louis Riel is an important and controversial figure in Canadian history. The Louis Riel I learned about in history class at school in he 1960s was portrayed as a rebel and traitor. Today, many historians sympathize with Riel as a Métis leader who fought for the rights of his people and recognize his contribution to the Manitoba becoming a province of Canada. This was the Riel my daughter learnt about at school in the early twenty-first century. The St. Boniface Museum is perhaps the best place in Winnipeg to learn about the life and impact of Louis Riel, but it’s not the only place. You can read more in my post Discovering Louis Riel in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

St. Boniface Museum is a modest-size museum with an extensive collection of historic artifacts, art, photographs, books and other information. It offers historic workshops, such a Métis beadwork or finger weaving, and hosts special art exhibits. It is a museum I like to revisit. I learn something each time. Check the museum site for the most current information on hours and workshops.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peeks ahead.

PIN IT

An interesting piece of history. I knew nothing about Winnepeg’s French and Metis communities. Reminds me of the Augustinian Monastary in Quebec that I recently visited. It was (and is still) a monastary that became Quebec’s first hospital and is now a museum.

Ken, it is an interesting piece of history. I haven’t been to the Augustinian Monastery in Quebec. It sounds like the kind of place I enjoy visiting.

What an interesting museum and history about Riel. We never seem to get over to the French side of Winnipeg when we visit – I guess I need to change that.

Cindy, crossing the river to the French side would be well worth it the next time you’re in Winnipeg. The St. Boniface Museum is worth a visit, as is Fort Gibraltar (open only in summer and during February’s Festival du Voyageur). There are some good restaurants too,

I know very little if French Canadian history. That said I really enjoyed the information you shared. I am also a huge fan of museums. This one looks impressive.

Susan, it is a lovely museum. I too am a fan of museums.

Very interesting museum, Donna. Just as I looked at your first picture, even before I began reading the post, I thought about the buildings of the French Quarter in New Orleans. Not surprisingly of course, since you say that Winnipeg has such a large French population.

Anda, the Red River Frame construction used in this population (and popular at the time) certainly had a French influence.

This was really fascinating, Donna since I know so little of the French-Canadian history and this was the first time I’d heard of the Métis Nation. Marie-Anne Guboury sounds like a incredibly resourceful woman and I was so glad to see a woman included in the frontier history as the part that women played has largely been ignored. I thought your comment about Louis Riel at the end of your post was also interesting as the history you and I learned growing up was so often dependent on the storyteller and politics of the time. Makes you wonder how it will be written in another century, doesn’t it? Anita

Anita, not only does it make me wonder what version will be told in another century, it makes me more aware that what we see and learn today is influenced by the perspective of the teller, something to keep in mind when visiting museums and historical sites.

Poor St. Boniface Cathedral! It kept burning down. It’s been a long time since I last read about Louis Riel and the importance in our country’s history.

Janice, history did seem to repeat itself. Fire seems to have been more of a threat to buildings like this in the past.

That’s a beautiful photo of the St. Boniface museum Donna. I sure do miss those sunny Manitoba skies.

Michele, it’s interesting you bring up Manitoba skies. I love the skies here – so broad, wide and expressive. And different each day. It was only after I started spending winters away that I began to truly appreciate the beauty of our sky.

What a great museum! Gives me another reason to head north. It looks like the exhibits are well staged with adequate information to really give you a feel for the history behind it. Love the story of Marie-Anne.

Thanks Rose Mary. There is a lot of interesting history here – I like how the museum illustrated that with stories of individual people and their lives.

The St. Boniface Museum looks really interesting. I never knew a log building could be that big! It’s wonderful to see that it still stands, especially given the story you tell of so many churches. The Metis culture particularly interests me: how a group of people could develop a distinct, cohesive, cultural identity in such a short time (historically speaking).

Rachel, I hadn’t thought about it before but it is interesting that the culture developed in a short period of time. Their history is not without its struggles for recognition.

The Boniface Museum looks fascinating. Thanks for the glimpse into French-Canadian history. It’s an area I could stand to learn more about, and such well-done museums are always a great help in that area.

Jeri, I am a big fan of museums – perhaps because I’ve been likely enough to visit some very well-done ones.

That is an impressive size for a log structure. I guess it must be sturdy since it’s still standing after all these years. This looks like exactly the type of museum that I enjoy. I don’t know much about this part of North America, so it would be very interesting to learn. I also like how the cathedral incorporates the old stone facade.

The architecture of the new cathedral is interesting – modern, yet incorporating the old stone facade.

Thank you for sharing St Boniface Museum. As a French Canadian from Quebec I’m familiar with the story of Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière and Marie-Anne Gaboury and of course Louis Riel but we didn’t really learn much about their effect on Western Canada. Thanks for this.

Glad you enjoyed reading this. It would be interesting to compare how Canada’s French-Canadian history is taught in Quebec versus western Canada.

Thank you. I understand that the museum was previously an orphanage. My mom and her three sisters worked at an orphanage in St. Boniface to help the nuns and it likely was the early 1900s. They were Mary, Margaret, Lily and Cecile Welsh and they returned home to their family in Saskatchewan with the outbreak of the Spanish flu with the exception of Cecile who succumbed to the flu. Their father Was Francis Welsh and his father was Norbert Welsh, from the book “The Last buffalo Hunter”. I always wondered if there were pictures of Norbert Welsh or of my mom and her sisters during their time at St. Boniface. I need to visit there.

Denise, it’s interesting to hear about your connection to the museum. If you do visit, I’d be interested in hearing if you find any photos or other things of interest related to your mother’s and aunt’s time working at the orphanage.

Hi Donna, I will certainly let you know. Thank you

There is a big error in your history facts. Louis Riel Jr. is not a descendant from Jean Baptiste Lagimodiere and one of his daughters from his native wife but rather from his daughter, Julie whom her mother was Anne Marie Gaboury. Louis Riel Jr’s mother is Julie Lagimodiere and his father is Louis Riel Sr. Please make the corrections asap.

Thanks Marie for pointing this out. I have updated the post.