Manitoba Legislature Statues And Colonialism

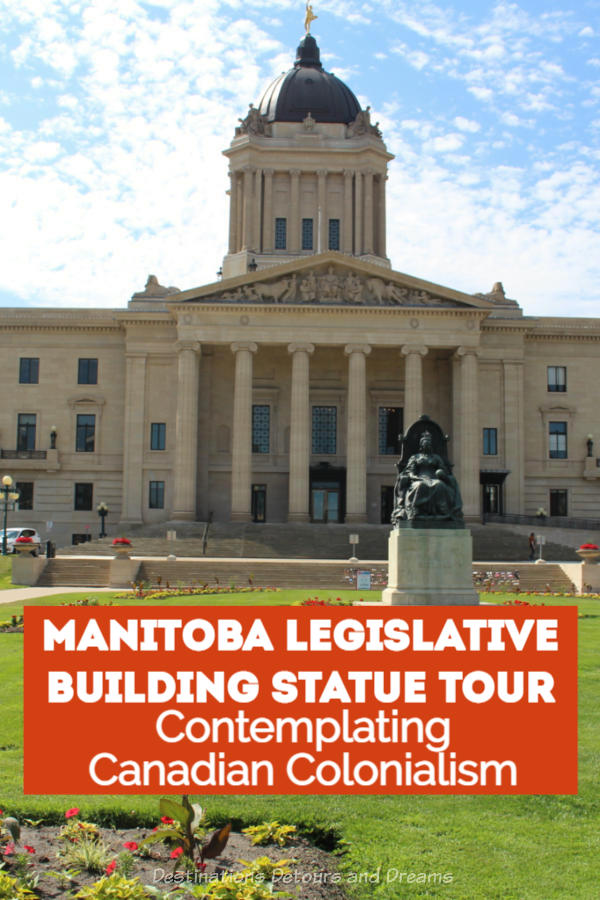

A tour of the statues on the grounds of the Manitoba Legislative Building prompts thoughts about the impact of Canadian colonialism on Indigenous peoples

I took this photo of the Queen Victoria statue in front of the Manitoba Legislature Building in Winnipeg on June 29, 2021. Two days later, on July 1, 2021, a crowd doused the statue with red paint and toppled it. Red painted handprints covered the base of the statues. A sign saying “We were children once. Bring them home.” was left on the statue’s pedestal. Later that night, someone decapitated the statue and dumped the head in the river.

Canada Day, a national holiday on July 1, commemorates the anniversary of the day in 1867 when the British North America Act created Canada. Celebrations in 2021 were muted. Many communities cancelled festivities or changed the focus to be more reflective after the horrific discoveries of more than 1,000 unmarked graves on sites of former residential schools.

Many Indigenous people, whose history on the land goes back thousands of years, have never celebrated Canada Day. European colonization had a devastating effect. Some view Canada as something imposed on them. Deep-seated systemic racism continues to this day. In 2019, Canada’s National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls concluded that Canada as a state is responsible for an ongoing genocide of Indigenous peoples.

Past and present atrocities include broken treaties, violence against women, bans against Indigenous culture, stripping women of their status, the Sixties Scoop mass removal of Indigenous children from their families into the child welfare system, the lack of clean safe drinking water in many Indigenous communities, and the residential school system. Attention on Canada Day 2021 focused on the residential school system.

Between the 1870s and 1997 the government forced many Indigenous children to attend church-run, government-funded schools. The children had to abandon their language and culture, learn English, accept Christianity, and embrace European customs. Removed from their parents, stripped of their culture, and malnourished, they lived in poor conditions where disease easily spread. Many also experienced physical and/or sexual abuse.

In late May 2021, news stories emerged about a survey of the grounds at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. The survey found the remains of 215 children buried at the site. Since then, ground penetrating radar has discovered unmarked graves on the sites of at least five other residential schools. Instead of celebrating Canada Day, many Indigenous and non-Indigenous people across the country attended rallies and protests.

In Winnipeg, thousands attended two separate rallies, a “No Pride in Genocide” rally and an “Every Child Matters” walk. That walk ended at the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds. Although the crowds on the grounds were largely peaceful, a small subset surrounded the Queen Victoria statue, wrapped it in ropes, and pulled it off its base.

Two days earlier, I had been on the grounds of the Legislature Building for a different reason. I was there on a self-guided tour of the statues. A physically-distanced outing after many weeks of “lockdown” and an opportunity to try out one of the Tripvia GPS-guided audio walking tours for a review I planned to write. Although outrage over the discovery of graves didn’t bring me to the grounds that day, it certainly coloured my experience.

The Beaux-Arts Classical Manitoba Legislative Building, covered in Manitoba Tyndall limestone, opened in July, 1920. Many allegorical works of art celebrating wisdom, justice, and courage adorn the building. Almost forty statues dot the beautifully landscaped grounds and Memorial Park across the street.

Except for the whimsical bears in the above photos, most of the statues are of people. In 2005, Manitoba artists designed sixty-two sponsored polar bears to be displayed that summer along Broadway Avenue as a Manitoba Cancercare fundraiser. Now you’ll find the bears in various places across the city and the province. Several stand on the grounds of the Manitoba Legislative Building.

Information plaques accompany a few of the others statues on the grounds, but most simply show the names of the subjects and, sometimes, the dates of their lives. A guide like the Tripvia audio tour I used provides more information on the subjects. There is also a walking tour brochure available from the Manitoba Government.

The Queen Victoria statue, erected in 1904, is/was the largest statue. Queen Victoria holds a sceptre in her right hand and an orb in her left. St. George, England’s patron saint, stands behind her crowned with a dove and holding a sword. Queen Victoria ruled the British Empire during the time Canada was formed, Manitoba became a province, and treaties were negotiated with Indigenous peoples. An ardent imperialist, she played a supporting role in the creation of Canada.

Statues adorn either side of the east and west entrances to the building. Statues of Major General James, the British commander at the 1759 Battle of the Plains of Abraham, and Lord Dufferin, Governor General of Canada from 1872-1878, sit at the west entrance.

Statues of Sieur de La Vérendrye and Thomas Douglas, the Fifth Earl of Selkirk, sit at the east entrance. La Vérendrye was one of the first European explorers to reach the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers in what is now Winnipeg. The Earl of Selkirk founded the Red River Settlement, a settlement of Scottish colonists on the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. Its boundaries crossed parts of what is now Manitoba and North Dakota in the U.S.

A statue of Louis Riel sits on the south grounds. Now recognized as a Founding Father of Manitoba, Riel remains a controversial figure. He has been portrayed as both a hero and a traitor. In this statue, he wears formal attire fitting for the era as well as a voyageur sash and moccasins to represent his Métis heritage. Read more about Louis Riel in my post Discovering Louis Riel in Winnipeg, Canada.

At first glance, you may wonder why statues of a nineteenth-century Ukrainian poet and an Icelandic statesman sit on the grounds of the Manitoba Legislative Building. Ukrainians are one of the largest ethnic groups in the province. Manitoba has the largest ethnic Icelandic population outside of Iceland. Icelanders emigrated to Manitoba in the 1800s and created their own community called New Iceland. Sigurdsson, an Icelandic statesman spearheaded the movement to secure Icelandic Independence from Denmark. An identical statue stands in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Other people commemorated in statues include Scottish poet Robert Burns, Marc-Amable Girard, Manitoba Premier in 1874, and Sir William S. Stephenson, the inspiration for the character of James Bond. A memorial remembers the victims of the Holocaust. Another memorial, dedicated on the fortieth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, honours the victims of war.

Nellie McClung was a well-known suffragette in Manitoba. The Nellie McClung Memorial features the Famous Five women (Louise McKinney, Irene Parlby, Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie McClung) whose actions led to the Persons Case. In 1929, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council overturned a Supreme Court of Canada decision. The Committee ruled that women were persons and eligible to be appointed to the Senate. This was an important ruling but it didn’t apply to all women. First Nations women did not receive the right to vote until 1960 and, until very recently, their Indigenous status depended upon whom they married.

As I ended my statue tour, I was struck by the complete absence of First Nations representation. The selection of statues on the grounds portrayed a settler’s perspective. What I saw and what I hadn’t seen reflected a willful blindness to Indigenous history and culture. Or, worse, an attempt to erase it.

The residential schools were indeed a deliberate attempt to erase Indigenous culture with explicit objectives of indoctrination and assimilation. The purpose was to eliminate all aspects of Indigenous culture.

Many Canadians expressed shock or disbelief at the discovery of the unmarked graves. In a number of news stories residential school survivors said they were not surprised and expected more graves would be found at other schools. Students disappeared. Conditions at the schools led to high mortality rates. The Department of Indian Affairs refused to ship home bodies for cost reasons.

Many non-Indigenous Canadians know very little about Indigenous history or the ways the legacy of colonization continues to affect the daily, everyday lives of Indigenous peoples. Although things are slowly changing, the official history has for years been the settlers’ version. Many of us know very little about the treaties which give us the right to live on this land. We have limited knowledge and understanding about the residential school system.

I was shocked to learn in my older adult years that residential schools and the Sixties Scoop had existed at the same time as I’d been attending school. I’d thought the residential school tragedy had occurred in the past, not in my lifetime. While writing this article, I asked my thirty-three-year-old daughter what she’d learned about residential schools. She remembered it being mentioned in school, but didn’t recall spending much time on it.

So, what will happen to the Queen Victoria statue? The Winnipeg Police continue to investigate the incident. At this point, I don’t know whether the statue can or will be restored. It is currently being assessed for damage. Whether the statue should be restored to its prominent spot on the Legislative Grounds is a matter of debate.

When I saw the Queen Victoria statue during my tour of the grounds, I remembered a 1990s visit of friends from England. They spent one week of their big three-week Canada trip with us in Winnipeg. The number of places and things in Canada named after Queen Victoria surprised Celia. “She must have done great things for Canada,” she said.

I don’t condone violence or the destruction of the statue, but the more I learn, the more I can understand the anger, frustration, trauma, and grief that led to the toppling of a symbol of Canada’s colonialism. Right now, many non-Indigenous Canadians express outrage and offer support to Indigenous peoples. Will that support extend beyond a few protest marches and orange shirt days?

We cannot undo the past, but we can change the present and shape the future. As we face the horrifying facts of our past, we must find a way to facilitate healing and move forward to a better future.

The University of Alberta offers an excellent online course called Indigenous Canada that explores indigenous histories and contemporary issues in Canada. You can audit the course for free. That means you have access to all the material, but you do not get grades on tests or get any credits. Although the course has been designed as a 12-week course with each week’s modules taking approximately two hours of time, you can proceed through the course at your pace.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission operated between 2007 and 2015 with a mandate to inform all Canadians about what happened in the residential schools and to facilitate reconciliation among former students, their families, their communities and all Canadians. Find the full text of their mandate here. The Commission travelled to all parts of Canada and heard from more than 6,500 witnesses. Find their report here. Of particular note is the document on Calls to Action.

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls looked into and reported on the systemic causes of all forms of violence against Indigenous women and girls, including sexual violence. Find their list of recommendations here.

I write this from my home in Winnipeg, Manitoba which is located in Treaty 1 Territory on the original lands of Anishinaabeg, Dakota, Oji-Cree, and Dene Peoples, and the homeland of the Métis Nation.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peeks ahead.

PIN IT

I also was shocked to learn that the residential schools still existed as recently as the 1990’s. Thanks for the history lesson.

Ken, I keep being shocked and appalled the more I learn.

Well done, Donna. A very enlightening piece.

Thanks Linda.

A difficult subject beautifully handled. I suspect there is another travel writing award in your future for this piece. Thanks for taking it on.

Thanks Cindy.