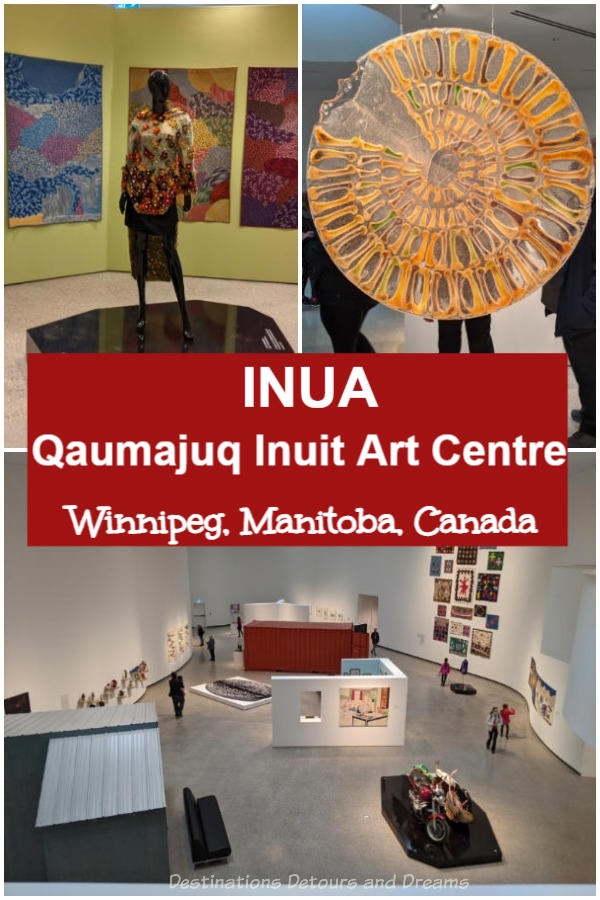

INUA: Inaugural Exhibition At Qaumajuq Inuit Art Centre

The inaugural show at Qaujamaq in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada features a diverse collection of Inuit art by over 90 Inuit artists

Update May2023: This exhibition is no longer running, but I have left the post active because it gives an overview into the diversity of Inuit art, which you can experience for yourself in current exhibitions at Qaumajuq.

The Winnipeg Art Gallery in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada has the largest public collection of traditional and contemporary Inuit art in the world. In March 2021, a new building Qaumajuq opened in which to showcase that art to the world. To find out more about this amazing space and the art it features, read my post Qaumajuq: Illuminating The Largest Collection of Inuit Art In The World. The rest of this post will focus on the inaugural exhibition, INUA, in its main gallery.

INUA features art by over 90 Inuit artists from across the Canadian north and the urban south as well as a selection of work from other circumpolar regions such as Greenland and Alaska. INUA has two meanings. It means spirit or life in many dialects across the Arctic. It is also the acronym for Inuit Nunangat Ungammuaktut Atautikkut or “Inuit Moving Forward Together.” It reflects the curators’ vision of Qaumajuq as a site to gather and share, be inspired by previous generations, and create new pathways forward in Inuit art. The works are an integration of old, modern, and contemporary that celebrate the past and speak to the present and the future.

The colourful embroidered wall hangings Four Seasons of Tundra (as pictured in the photograph at the top of this post) greet you as you enter the gallery and draw attention to the changing seasons of the land. The piece of clothing art on the mannequin standing in front of the hangings is Our Flourishing Culture by Maata Kyak. It is made of silk, embroidery lace, dyed sealskin, beads, and pearls.

The four curators of INUA represent the four regions of Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit territories of Canada: the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (northern Northwest Territories), Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec), and Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador). Dr. Heather Igloliorte is an Inuk from Nunatsiavut. Krista Ulujuk Zawadski was raised in Chesterfield Inlet and now lives in Rankin Inlet, both of which are in Nunavut. Kablusiak is a multi-disciplinary Inuk artist who was born in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, was raised in Edmonton, Alberta, and is now based in Calgary, Alberta. Asinnajaq is an Inuk filmmaker and visual artist from Nunavik.

One of the first installations you see in the exhibition is a collection of four works, organized from west to east in terms of the regions they come from. Each of these works has a personal connection to the curators. Artist Ella Nasogak Nasogakaluak-Brown, whose two handmade dolls of mixed media titled Arnaq & Angun are on display, is the grandmother of curator Kablusiak. A carving of ivory, whale bone, and wood entitled Carved Tusk on Base was created by curator Krista Ulujuk’s great-grandfather Victor Sammurtok. Curator Asinnajaq’s great-aunt Ellsapi Uppatitslaq Inukpuk is the artist who created Woman Adopts a Caterpillar, two dolls wearing fur clothing. The beaded purse made of tanned hide and fabric was created by Suzannah Igoliorte, the grandmother of curator Dr. Heather Igloliorte.

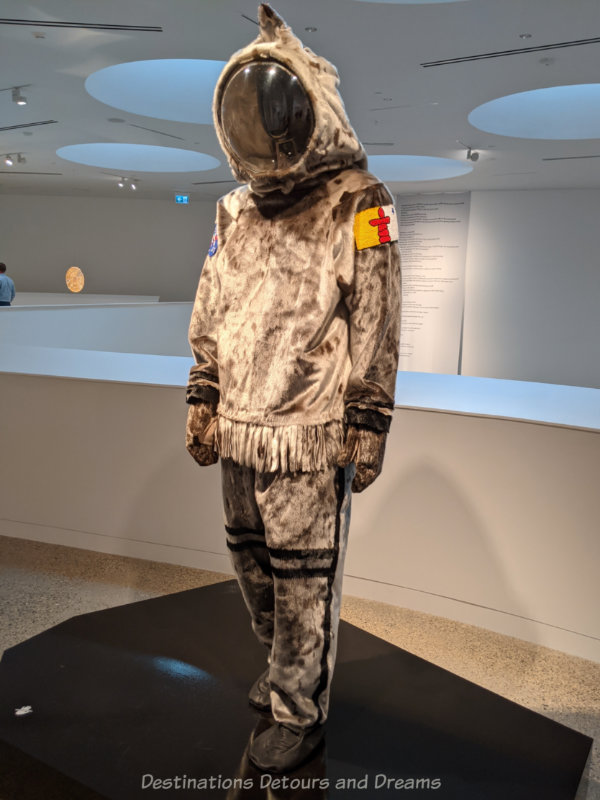

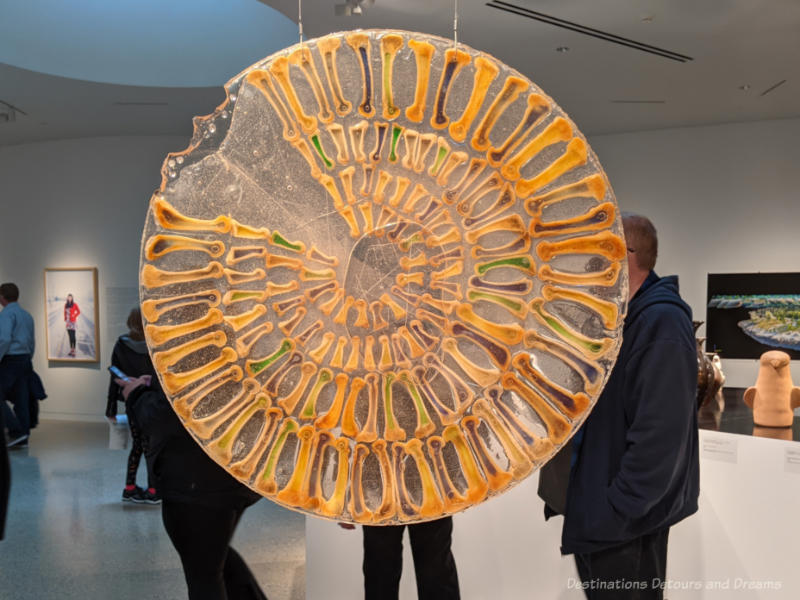

I was impressed by the diverse collection showcased in this exhibition, both in terms of styles and of materials used. There were what I consider more traditional works, such as the wall hangings in the above photos. There were modern and contemporary pieces using traditional materials. There were pieces created with new media. All reflected the Inuit experience. I can best illustrate that diversity by showing photographs of some of the art work.

Art becomes more meaningful and powerful when you know the stories behind the works. The carving entitled W_3-1258 by Bill Nasogaluak is a self-portrait with his Eskimo identification number. (Note the term Eskimo is now considered derogatory in Canada.) In Inuit tradition, a child is given a one-word name. The child may be named after ancestors or family friends. When fur traders began to move further north bringing missionaries and government agencies with them, the people in those agencies had trouble understanding the naming system and difficulty pronouncing the names. Starting in the late 1920s, officials tried various methods to deal with their own confusion. They standardized spelling, created separate files with the name in English and syllabic characters, and did fingerprinting. The identification disc system was adopted in 1941. Every Inuit was assigned a number on a disc to be worn at all times or sewed into his clothing. The number was used in all official documentation. In 1968, the Northwest Territories Government introduced “Project Surname” to persuade all Inuit adults to adopt and register a family name. By 1972, the disc system was discontinued in the Northwest Territories and gradually phased out in other regions.

More of the naming issue can be found in one of pictures on the wall of the above recreated home. A framed newspaper clipping from the Globe and Mail December 1, 2001 tells the story of an Edmonton man who won the right to go back to using his one-word name. He received the name Kiviaq from his parents in 1936. When he, his mother, and his sister were taken from the North to Alberta shortly after he was born, his birth was recorded under the name David Ward. In September 2000, he applied to change his name back to Kiviaq. His original request was rejected because Alberta law requires both first and last names. He appealed to the Government Services Minister, who granted his request saying, “Your current legal name marks your loss of contact with the community of your birth. You wish now to formally reassert this personal connection to your culture by taking the name you were given when you were born.”

I hope the photos I’ve shared give you an idea of the vibrancy and diversity of the art in this exhibition. INUA runs at Qaumajuq until February 2023.

Never miss a story. Sign up for Destinations Detours and Dreams free monthly e-newsletter and receive behind-the-scenes information and sneak peeks ahead.

PIN IT

I am also impressed with the diversity of pieces in this exhibit. Those that really caught my eye include the shipping container, the motorcycle and the Bronson Jacque paintings. None are anything like my uninformed image of what Inuit art is like.

Ken, I have to admit the exhibition also challenged my preconceptions. I too was impressed with the diversity in the exhibit.